Slides from my talk at the OARN 2012 conference on augmented reality.

This is the connected world, a journal by Gene Becker of Lightning Laboratories focusing on the confluence of ubiquitous computing, augmented reality, social media & the internet of things.

Slides from my talk at the OARN 2012 conference on augmented reality.

Just got back from Sammy Global HQ in Seoul. It was a great trip & the weather’s perfect right now. Here’s a morning shot from the hotel:

An arresting QR code seen in the subway:

And here’s a nighttime street scene, Gangnam style, yo.

Glad to be back on terra recognita, although I have no idea what time zone the rest of me is in right now.

As long-time TCW watchers know, we do love the concert scene. In the last 3 months we’ve had the good fortune to be up close for 3 very different shows:

Red Hot Chili Peppers in Oakland, CA. This was originally slated for April but was postponed to August after Anthony Kiedis broke his foot. Fantastic show, hey oh!

The Tedeschi-Trucks Band in Saratoga, CA. They brought a big band and a big noise. Some of Susan’s material, some of Derek’s and some from the togetherness band. DTB is one of my favorites this year, and this show did not disappoint.

Peter Gabriel Back to Front Tour, San Jose, CA. Still one of the most creative artists in the world, even if he does look like a portly elder statesman these days. Fabulous show, as seen from 3rd row center. Bonus tech-relevant item: each musician had a Kinect mounted at their position, used to capture & project new-aesthetic-vibe imagery on the screen behind.

Photo from May 19, 2005: Came across this old RoomWizard at IDEO. It was designed by my former HP Labs colleagues Bill Sharpe & Ray Crispin at the Appliance Studio, based on the HPL RoomLooker prototype conference room appliance.

I remembered this picture today when I heard the sad news that Bill Moggridge had passed from this earth. Farewell to a legendary designer…

This is:

1. A blog post of an image of a tweet of an instagram of a screenshot of an image of an augmented reality dog from an animated Japanese television show in a simulated gilt picture frame on a simulated wall of a simulated 3D gallery in an augmented reality experience launched in California from a hidden URL printed in UV ink in an advertisement for an augmented reality company in Amsterdam in a comic book designed in London as “an investigation into perception, storytelling and optical experimentation.”

2. Densuke.

The concept video of Google’s Project Glass has whipped up an Internet frenzy since it was released earlier this week, with breathless coverage (and more than a little skepticism) about the alpha-stage prototype wearable devices. Most of the reporting has focused on the ‘AR glasses’ angle with headlines like “Google Shows Off, Teases Augmented Reality Spectacles“, but I don’t think Project Glass is about augmented reality at all. The way I see it, Glass is actually about creating a new model for personal computing.

The concept video of Google’s Project Glass has whipped up an Internet frenzy since it was released earlier this week, with breathless coverage (and more than a little skepticism) about the alpha-stage prototype wearable devices. Most of the reporting has focused on the ‘AR glasses’ angle with headlines like “Google Shows Off, Teases Augmented Reality Spectacles“, but I don’t think Project Glass is about augmented reality at all. The way I see it, Glass is actually about creating a new model for personal computing.

Think about it. In the concept video, you see none of the typical AR tropes like 3D animated characters, pop-up object callouts and video-textured building facades. And tellingly, there’s not even a hint of Google’s own Goggles AR/visual search product. Instead, what we see is a heads-up, hands-free, continuous computing experience tightly integrated with the user’s physical and social context. Glass posits a new use model based on a novel hardware platform, new interaction modalities and new design patterns, and it fundamentally alters our relationship to digital information and the physical environment.

This is a much more ambitious idea than AR or visual search. I think we’re looking at Sergey’s answer to Apple’s touch-based model of personal computing. It’s audacious, provocative and it seems nearly impossible that Google could pull it off, which puts it squarely in the realm of things Google most loves to do. Unfortunately in this case I believe they have tipped their hand too soon.

Let’s suspend disbelief for a moment and consider some of the implications of Glass-style computing. There’s a long list of quite difficult engineering, design, cultural and business challenges that Google has to resolve. Of these, I’m particularly interested in the aspects related to experience design:

Continuous computing

The rapid adoption of smartphones is ample evidence that people want to have their digital environment with them constantly. We pull them out in almost any circumstance, we allow people and services to interrupt us frequently and we feed them with a steady stream of photos, check-ins, status updates and digital footprints. An unconsciously wearable heads-up device such as Glass takes the next step, enabling a continuous computing experience interwoven with our physical senses and situation. It’s a model that is very much in the Bush/Engelbart tradition of augmenting human capabilities, but it also has the potential to exacerbate the problematic complexity of interactions as described by polysocial reality.

A continuous computing model needs to be designed in a way that complements human sensing and cognition. Transferring focus of attention between cognitive contexts must be effortless; in the Glass video, the subject shifts his attention between physical and digital environments dozens of times in a few short vignettes. Applications must also respect the unique properties of the human visual system. Foveal interaction must co-exist and not interfere with natural vision. Our peripheral vision is highly sensitive to motion, and frequent graphical activity will be an undesirable distraction. The Glass video presents a simplistic visual model that would likely fail as a continuous interface.

Continuous heads-up computing has the potential to enable useful new capabilities such as large virtual displays, telepresent collaboration, and enhanced multi-screen interactions. It might also be the long-awaited catalyst for adoption of locative and contextual media. I see continuous computing as having enormous potential and demanding deep insight and innovation; it could easily spur a new wave of creativity and economic value.

Heads-up, hands-free interaction

The interaction models and mechanisms for heads-up, hands-free computing will be make-or-break for Glass. Speech recognition, eye tracking and head motion modalities are on display in the concept video, and their accuracy and responsiveness is idealized. The actual state of these technologies is somewhat less than ideal today, although much progress has been made in the last few years. Our non-shiny-happy world of noisy environments, sweaty brows and unreliable network performance will present significant challenges here.

Assuming the baseline I/O technologies can be made to work, Glass will need an interaction language. What are the hands-free equivalents of select, click, scroll, drag, pinch, swipe, copy/paste, show/hide and quit? How does the system differentiate between an interface command and a nod, a word, a glance meant for a friend?

Context

Physical and social context can add richness to the experience of Glass. But contextual computing is a hard problem, and again the Glass video treats context in a naïve and idealized way. We know from AR that the accuracy of device location and orientation is limited and can vary unpredictably in urban settings, and indoor location is still an unsolved problem. We also know that geographic location (i.e., latitude & longitude) does not translate to semantic location (e.g., “in Strand Books”).

On the other hand, simple contextual information such as time, velocity of travel, day/night, in/outdoors is available and has not been exploited by most apps. Google’s work in sensor fusion and recognition of text, images, sounds & objects could also be brought to bear on the continuous computing model.

Continuous capture

With its omnipresent camera, mic and sensors, Glass could be the first viable life recorder, enabling the “life TiVo” and total recall capabilities explored by researchers such as Steve Mann and Gordon Bell. Continuous capture will be a tremendous accelerant for participatory media services, from YouTube and Instagram-style apps to citizen journalism. It will also fuel the already heated discussions about privacy and the implications of mediated interpersonal relationships.

With its omnipresent camera, mic and sensors, Glass could be the first viable life recorder, enabling the “life TiVo” and total recall capabilities explored by researchers such as Steve Mann and Gordon Bell. Continuous capture will be a tremendous accelerant for participatory media services, from YouTube and Instagram-style apps to citizen journalism. It will also fuel the already heated discussions about privacy and the implications of mediated interpersonal relationships.

Of course there are many other unanswered questions here. Will Glass be an open development platform or a closed Google garden? What is the software model — are we looking at custom apps? Some kind of HTML5/JS/CSS rendering? Will there be a Glass equivalent to CocoaTouch? Is it Android under the hood? How much of the hard optical and electrical engineering work has already been done? And of course, would we accept an even more intimate relationship with a company that exists to monetize our every act and intention?

The idea of a heads-up, hands-free, continuous model of personal computing is very interesting, and done well it could be a compelling advance. But even if we allow that Google might have the sophistication and taste required, it feels like there’s a good 3-5+ years of work to be done before Glass could evolve from concept prototype into a credible new computing experience. And that’s why I think Google has tipped their hand far too soon.

That was quick. No sooner do I say:

That was quick. No sooner do I say:

On further reflection, I suppose there’s some long-term risk that by focusing on human-centricity I’m making a Ptolemaic error. Maybe at some point we’ll realize that information is the central concern of the universe, and we humans are just a particularly narcissistic arrangement of information quanta.

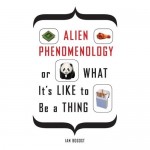

Than I come across Ian Bogost’s new book, Alien Phenomenology:

Humanity has sat at the center of philosophical thinking for too long. The recent advent of environmental philosophy and posthuman studies has widened our scope of inquiry to include ecosystems, animals, and artificial intelligence. Yet the vast majority of the stuff in our universe, and even in our lives, remains beyond serious philosophical concern.

In Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing, Ian Bogost develops an object-oriented ontology that puts things at the center of being—a philosophy in which nothing exists any more or less than anything else, in which humans are elements but not the sole or even primary elements of philosophical interest. And unlike experimental phenomenology or the philosophy of technology, Bogost’s alien phenomenology takes for granted that all beings interact with and perceive one another.

Not sure if this will change anything for me, but I’m open to the journey. Click.

In my last post, I wrote:

So if there’s a major transition this industry needs to go through, it’s the shift from a box-centered view of personal computers, to a human-centered view of personal computing.

Folks, it’s 2012. I shouldn’t even have to say this, right? We all know that personal computing has undergone a radical redefinition, and is no longer something that can be delivered on a single device. Instead, personal computing is defined by a person’s path through a complex melange of physical, social and information contexts, mediated by a dynamic collection of portable, fixed and embedded digital devices and connected services.

‘Personal computing’ is what happens when you live your life in the connected world.

‘Human-centered’ means the central concern of personal technology is enabling benefits and value for people in their lives, across that messy, diverse range of devices, services, media and contexts. Note well, this is not the same as ‘customer-centered’ or ‘user-centered’, because customer and user are words that refer to individual products made by individual companies. Humans live in the diverse ecosystem of the connected world.

If you haven’t made the shift from designing PCs, phones and tablets to enabling human-centered personal computing, you’d better get going.

Lately we have seen a spate of pronouncements from industry executives, analysts & pundits about the so-called ‘post-PC’ era. Now, I completely understand the competitive, editorial and PR value of declaring The Next New Thing. But in using the term ‘post-PC’, these nominal thought leaders are making a faulty generalization and committing a category error in order to serve up a simplistic, attention-getting headline.

The faulty generalization is obvious. We’re no more ‘post-PC’ than we are ‘post-radio’, ‘post-book’, or ‘post-friends’. Are new devices and software platforms displacing some usage of desktop and notebook PCs? Of course. Are some companies going to rise and fall as a result? Sure, but are we witnessing the demise of PCs as a product category? Not even close.

Of more concern to me is the category error inherent in ‘post-PC’ thinking. ‘Post-PC’ is a narrative about boxes: PC-shaped boxes being superseded by phone- and tablet-shaped boxes. It’s understandable, since most PC, phone and tablet companies define and structure themselves around the boxes they produce; analysts count boxes and reviewers write articles about the latest boxes. But people who buy and use these devices don’t want boxes per se; they want to listen to music, play games, connect with friends, find someplace to eat, write some code or get their work done, whenever and wherever and on whatever device it makes the most sense to do so. This ‘post-PC’ notion is disconnected from the real value that people are seeking from their investment in technology products.

So if there’s a major transition this industry needs to go through, it’s the shift from a box-centered view of personal computers, to a human-centered view of personal computing. If I was running a PC company, that’s the technical, operational and cultural transformation I’d be driving in my every waking moment.